One way they could live the dream was through images of the kind seen in “Streams and Mountains Without End: Landscape Traditions of China” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The show, which will be on view through Jan. 6 in the Chinese paintings and calligraphy galleries, is technically a collection reinstallation spiced with a few loans. But the Met's China holdings are so broad and deep that some of the pictures here are resurfacing for the first time in almost a decade; one is finally making its debut a century after it was acquired. And there's more than just painting on view.

A longing for the natural world, or some version of it, real or ideal, saturated Chinese elite culture. Images of it turned up everywhere - on porcelain vases, cloisonne bowls, silk robes and jade sculptures. The most effective medium for imaginatively entering a landscape, though, was painting, and specifically in two forms, the hanging scroll and the hand scroll, both traditionally done in ink on silk.

The show opens with a hanging scroll: vertical, monumental, as tall as a door; you see it, and read it, from a long gallery away. Titled “Viewing a Waterfall From a Mountain Pavilion” and dated 1700, it's by Li Yin, a talented jobber who supplied art for the Qing dynasty equivalent of McMansions. The scene depicted is a narrow rocky gorge in which we, as viewers, are positioned low and looking up. A bit above us is a peaked-roof pavilion on a rock. Two men stand on its terrace taking in the scene.

And quite a scene it is. Cliffs soar skyward; torrents stream down. This is a nature as a theater of big, dwarfing effects. And it's charged with a weird, creaturely energy. Trees claw the air like dragons. The rock the pavilion rests on looks like some giant pachyderm. The world isn't just alive here; it's sentient, reactive. The men on the terrace appear unperturbed, but surely inwardly, like us, they're thrilled.

Hanging scrolls deliver their basic image fast - pow! - then leave you to sort out details. A second form of landscape painting, the hand scroll, operates on different dynamic. When viewed as intended, slowly unrolled on a tabletop, one section at a time, it's a cinematic experience, about anticipation, suspense, what’s coming next.

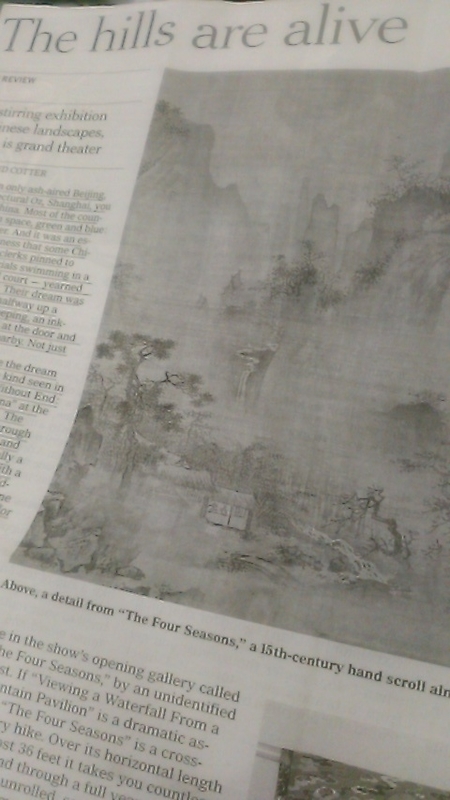

There’s a classic 15th-century example in the show’s opening gallery called “The Four Seasons,” by an unidentified artist. If “Viewing a Waterfall From a Mountain Pavilion” is a dramatic ascent, “The Four Seasons” is a cross-country hike. Over its horizontal length of almost 36 feet it takes you countless miles and through a full year. At the Met, it's unrolled, so you get the idea of a panorama right away. But the real pleasures lie in walking the walk.

The journey starts from the far right. It's spring, and sights come fast - a tiny waterfall, budding trees, a curl of smoke. Then you see summer workers hauling a boat by a whisker-fine rope. Mountains loom, contoured like muscles; they're worth a pause. Then openness. Sky, sky, sky, until its whiteness shades into autumn mist, which shades into what may be an iced-over lake. Winter: scratchy trees; hunkered-down houses; lamps in windows. And all the way to left, at the scroll’s edge, a bridge ends mid-arch, leading where? Back to Spring.

The stylistic variations possible within these two formats are practically endless. So are the thematic uses - personal, historical, political and practical - to which landscape images can be put. Joseph Scheier-Dolberg, an assistant curator in the museum’s Asian art department, has designed the show to give a sense of all this.

In a section called “The Poetic Landscape,” he links nature painting to Chinese literary tradition. Common to both was a goal of making mood - existential atmosphere - primary content. A 14th-century hanging scroll by the Yuan painter Tang Di is based on a couplet by the famed poet Wang Wei (A.D. 699-759).

I walk to where the water end

And sit and watch as clouds arise.

Tang’s landscape, gnarly, dark and Gothic, catches the couplet’s depressive tread.

Some poem-picture pairings play with contrasts. Another great early poet. Li Bo (701-762), wrote about a journey he took to Sichuan, anciently known as Shu. The trip, as he described it, was a killer, up hellish mountains, along sheer-drop paths. But a paint response to his poem by the 18th-century artist Gu Fuzhen makes the experience feel festive, fun.

As time went on, landscape images were less and less based on nature observed and more and more on old paintings. The Ming dynasty artist and theorist Dong Qichang (1555-1636) systemized a practice of simultaneously channeling and customizing the work of past masters. And in a section of the show, “The Art-Historical Landscape,” Dong presides over a star-studded echo chamber of acolytes, who emulate him emulating earlier art.

The stylistic variations possible within these two formats are practically endless. So are the thematic uses - personal, historical, political and practical - to which landscape images can be put. Joseph Scheier-Dolberg, an assistant curator in the museum’s Asian art department, has designed the show to give a sense of all this.

In a section called “The Poetic Landscape,” he links nature painting to Chinese literary tradition. Common to both was a goal of making mood - existential atmosphere - primary content. A 14th-century hanging scroll by the Yuan painter Tang Di is based on a couplet by the famed poet Wang Wei (A.D. 699-759).

I walk to where the water end

And sit and watch as clouds arise.

Tang’s landscape, gnarly, dark and Gothic, catches the couplet’s depressive tread.

Some poem-picture pairings play with contrasts. Another great early poet. Li Bo (701-762), wrote about a journey he took to Sichuan, anciently known as Shu. The trip, as he described it, was a killer, up hellish mountains, along sheer-drop paths. But a paint response to his poem by the 18th-century artist Gu Fuzhen makes the experience feel festive, fun.

As time went on, landscape images were less and less based on nature observed and more and more on old paintings. The Ming dynasty artist and theorist Dong Qichang (1555-1636) systemized a practice of simultaneously channeling and customizing the work of past masters. And in a section of the show, “The Art-Historical Landscape,” Dong presides over a star-studded echo chamber of acolytes, who emulate him emulating earlier art.

As cities grew larger and more crowded, and a socially aspiring merchant class came to power, the age-old custom of building private formal gardens - enclosed, compressed, designer landscapes - gained popularity. Such gardens became frequent subjects of paintings, and two examples in the show are notable.

One, a small, crinkly hand scroll by a 19th-century artist named Yang Tianbi, is on first-time view at the Met, though it's did so almost by accident. The painting made an inconspicuous arrival in 1902, rolled up and stuck in a brush holder that had come with a cache of jade carvings. Now, 115 years later, it takes a public bow.

A second, much larger hand scroll, by the contemporary Beijing painter Hao Liang (born 1983), came to the collection just this year, and it's an arresting sight. An extended, ghostly-gray, almost anime-style vision of mythical gardens past - including Wang Wei’s - it ends with garish 21st-century development: a garden as an amusement park, with an immense, robotic Ferris Wheel spewing riders off into space.

The art in the show’s concluding section, “The Riverscape,” is historical but feel familiar, like recently heard news. No more poetry, or, not much. Here the image of nature is a political tool: a survey map, a surveillance device, a deed of ownership. A supersized 18th-century hand scroll, one of a set of 12 titled “The Qianlong Emperor’s Southern Inspection Tour,” documents a real event, an imperial tour that took place in 1751.

In the painting, the greater ruler shows up in the provinces, somewhere along a rain-swollen Yellow River, to ceremonially review a flood prevention project. The visit draws a strangely dutiful, cheerless local crowd. It's as if everyone knows what's really happening - a leader is reasserting a claim to his realm; to his own, personal streams and mountains without end. And yet, as everywhere in this lovely show, nature has a final word. The emperor, doing his emperor thing, is little more than a dot against the river behind him, which rolls on.

One, a small, crinkly hand scroll by a 19th-century artist named Yang Tianbi, is on first-time view at the Met, though it's did so almost by accident. The painting made an inconspicuous arrival in 1902, rolled up and stuck in a brush holder that had come with a cache of jade carvings. Now, 115 years later, it takes a public bow.

A second, much larger hand scroll, by the contemporary Beijing painter Hao Liang (born 1983), came to the collection just this year, and it's an arresting sight. An extended, ghostly-gray, almost anime-style vision of mythical gardens past - including Wang Wei’s - it ends with garish 21st-century development: a garden as an amusement park, with an immense, robotic Ferris Wheel spewing riders off into space.

The art in the show’s concluding section, “The Riverscape,” is historical but feel familiar, like recently heard news. No more poetry, or, not much. Here the image of nature is a political tool: a survey map, a surveillance device, a deed of ownership. A supersized 18th-century hand scroll, one of a set of 12 titled “The Qianlong Emperor’s Southern Inspection Tour,” documents a real event, an imperial tour that took place in 1751.

In the painting, the greater ruler shows up in the provinces, somewhere along a rain-swollen Yellow River, to ceremonially review a flood prevention project. The visit draws a strangely dutiful, cheerless local crowd. It's as if everyone knows what's really happening - a leader is reasserting a claim to his realm; to his own, personal streams and mountains without end. And yet, as everywhere in this lovely show, nature has a final word. The emperor, doing his emperor thing, is little more than a dot against the river behind him, which rolls on.